At The Interstices Between Harm and Hope

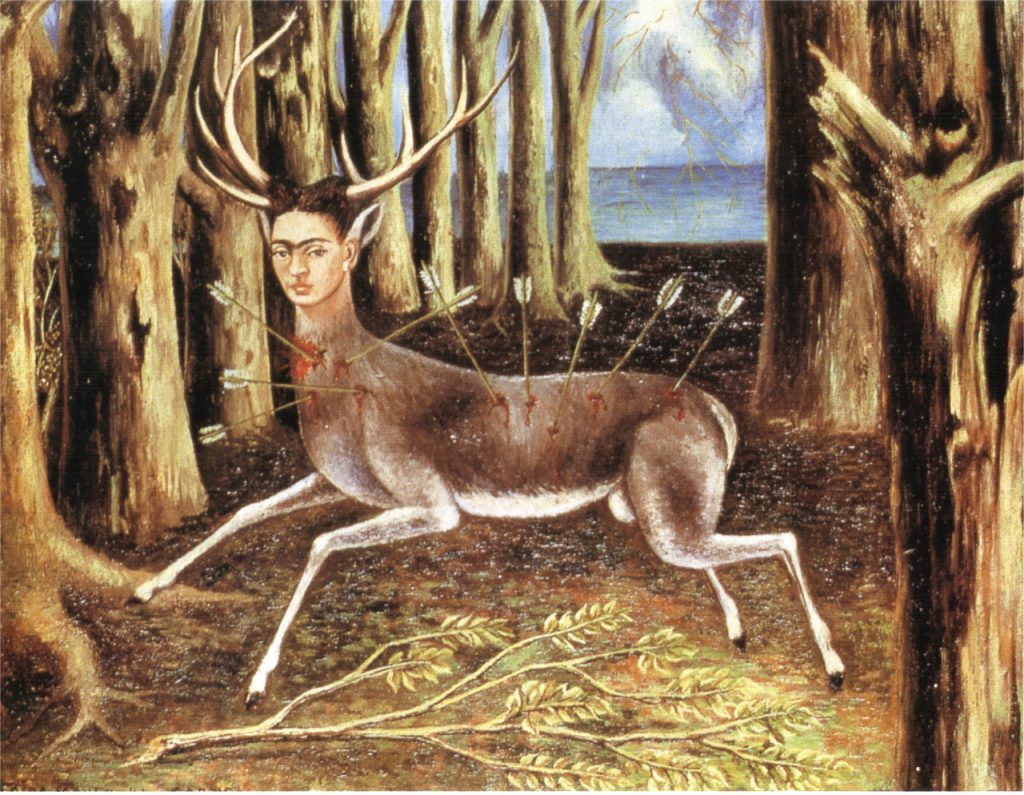

Frida Kahlo’s self-portrait “The Wounded Deer” (1946) speaks to this project’s many contradictions. This emotional painting depicts a flirtation with death—a frequent theme in Kahlo’s artistic work—but this piece in particular is a more literal expression of pain and a near-death experience: a perfect image to help me further elaborate on how we as clinicians understand suffering and in particular Latinas’ suicidal ideations and behaviors.

What are the possible connections between this painting and young Latinas who are in pain and/or suicidal? As Kahlo’s painting suggests, Latina girls who are suicidal are harmed in a myriad of ways, from different and mostly invisible sources. As in the painting, their pain is displayed openly and made public; frequently others, such as friends, teachers, and family members are aware of their pain. And as in Kahlo’s painting, the degree of harm experienced and portrayed by these women has the potential to blind observers and witnesses from any signs of hope.

At first glance we see the wounded body of a young deer taking center stage in this painting. There are nine arrows piercing his skin, and he is bleeding from the injuries. Kahlo’s head is on the deer’s body, and the deer is suspended in the air as if he is running through the corner of a dreary-looking forest surrounded by the sea. Large antlers extend from either side of Kahlo’s head as she faces us with a blank expression. A closer look reveals a fallen branch lying beneath Kahlo and, in the foreground, a tree with a branch broken off.

In this painting Kahlo might be understood as performing pain and a near-death experience; her surroundings might not seem to offer much opportunity to escape. She can be seen as trapped by her pain and her helplessness. She has been stabbed not by one, but by nine arrows. She is a stag, a male, frequently hunted. There are multiple hazardous circumstances compromising her safety and well-being.

However, details in the painting may provide bases for a different interpretation. It is the lens that the observer uses to appraise the situation that determines whether there is any hope for Kahlo. For those looking for strength in “The Wounded Deer,” Kahlo’s face offers an important point of entry. There, the observer can find a profound contradiction between Kahlo’s stoic expression and the pain of her bleeding body pierced by the arrows. She looks directly at the observer. Is she commanding their attention? Their pity? Their outrage? Or simply their witnessing? As observers, we cannot be sure. Her stare has the potential to invoke all these feelings and more, and in that process, as observers we may miss how Kahlo’s face reflects no anguish, that her neck and head are upright and alert, that her body seems in motion despite of her injuries, and that she has the body of a stag along with antlers, a symbol of strength.

In social work practice, the strengths perspective has emerged as an alternative to the more common pathology-oriented approach to helping clients. Instead of focusing on clients’ problems and deficits, the strengths perspective centers on clients’ abilities, talents, and resources. The social worker practicing from this approach concentrates wholly on identifying and eliciting the client’s strengths and assets in assisting them with their problems and goals.

Obviously, people in professions, such as social work, known for studying and ameliorating human problems, are increasingly attracted to what has become a new paradigm, a new way of thinking about and working with human beings across the lifespan that focuses on assets instead of deficits and on working in partnership “with” instead of doing “to.” (Saleebey, 2006, p197 )

Has the research on young Latinas’ suicidal ideations and behaviors been framed from a deficit perspective, the same way Kahlo’s self-portrait can be framed by observers whose gaze missed signals of resilience? I believe for the most part it has. For observers of “The Wounded Deer,” as for clinicians, researchers, politicians, and others, the way we look determines what we see. The strength-based approach is actually a frame. How likely is it that a change in frame–from pathology to strength–would happen in cases of suicidal risk? I am not sure. The fear of suicide may undermine our best efforts to abandon pathology-based perspectives. The fear of possible or actual harm might have the capacity to shake our faith in the capability of individuals, families, and communities.

We know that young Latinas as a group do not have much access to mental health services, and when they do, these services may not be responsive to their needs. How is it that young Latinas–having the highest levels of depression, suicidal ideation, and actual attempts compared to other groups of girls of different ethnicities and races, and having limited access to and use of health services–do not have the highest suicide rates? As I mentioned in another post, the gap in these numbers not only challenges the ideation-to-action framework of suicide, but it may be also an indication that we are missing something of significance. By studying Latinas exclusively when they are or were recently suicidal, we may be missing the opportunity to take a broader look at how they are thriving in spite of their pain and suffering.

For one thing, when we look online we find that young Latinas seem to be creatively managing their emotional pain, as indicated by the number of digital artistic productions–photography, theater, poetry, songwriting, dance, and video–as vehicles of expression of their suffering and resilience. As one of the actresses in the play Yo soy Eva tells us: “lo mas que sufro, lo más fuerte que me convierto,” which translates to “The more I suffer, the stronger I become.”

A unique opportunity to witness an alternative narrative, one based on empowerment and political organizing of Young Latinas, is in the documentary Ovarian Psycos. It tells the story of a fierce crew of women of color who have organized a bike brigade to fight violence against women in East L.A., California, the home of the Chicano movements of the 60s and 70s. The “Ovas,” as they call themselves, ride the streets at night for the purpose of their own healing, reclaiming their neighborhoods, and creating safer spaces for women.

In this documentary, the Ovas are not only giving testimony, but also rewriting their historic and present-day struggles against oppressions as nonwhite women. Most importantly, they are relying on their own ways of knowing: the kind of knowing that comes from their own life experiences. By doing that, they resist dominant racist, sexist, classist, and heterosexist paradigms, in both U.S. culture and Mexican-American communities. Also, they identify the effects of colonialism as it continues to thrive within the U.S. border in new, complex, and invisible forms.

In the enacting of their political agenda, the Ovas’ performances of defiance and resistance are strategically, intentionally, and unapologetically breaking with many expected social norms, stereotypes, traditions, and legacies. For the Ovas, their fight is not a mere fight for equality; their fight is a fight for justice.

How do the Ovarian Psycos make such a formidable break from these firmly engrained social practices? They do it by talking from the margins and a position of exclusion; by building solidarity, connections, and community; by reclaiming their cultural and spiritual native/Mexican roots; and by breaking with stereotypical expectations of femininity within their families and communities.

These strategies are not accidental; they have been evolving in the everyday lives of women in the Chicano community as well as in the writings of feminist Chicana activist/authors. In the following video, I connect the two: the Ovas’ daily struggle and what they are constantly learning from those experiences, and what feminist Chicana writers have said about similar experiences.