To what culture would Latinas’ suicidal ideations and attempts be bound?

“Is Culture To Blame for High Latina Suicide Attempt Rates?” This is the actual title of an article published by NewsTaco, a Latino online source which provides innovative and insightful news, critique, analysis, and opinions. The headline of the article is significant as it reflects what by August 2010 had already been identified as the reason why young Latinas had the highest level of suicidal behavior among their peers from other ethnicities.

By the time the NewsTaco piece was published, the story of teen Latinas’ high levels of suicidal ideations and attempts had been more than five years in the making. It had been covered by major news sources such as El Diario/La Prensa, WNYC, Latino USA, and a few blogs, including hispanictrending and juddandjason. Academic literature has traditionally identified the following as participating factors in poor mental health outcomes for young Latinas: immigration status, young Latinas living in two separate cultural realities, young Latinas being burdened by traditional cultural and religious beliefs from their country of origin, teen pregnancy, having too many adult responsibilities, acculturation stress, the generation gap, prescribed gender roles, and poor communication with mothers. On one way or another, all these factors are connected with the concept of acculturation. These themes had already become part of media and news conversations before the NewsTaco article was published. NewsTaco’s article not only continues these conversations, but more importantly zooms in on Latino culture as the main source of emotional pain for young Latinas, and as a possible cause of their high levels of suicidal behavior.

Dr Luis Zayas, a leading researcher on the topic was interviewed for the article, and his answers further cement what earlier news reports seemed to have already concluded. This was his answer to the interviewer’s question about whether he had reached any conclusive findings during his 20-year project:

We always felt that some cultural factors played a part in the higher than average rate of attempts by young Latinas. What we came down on is acculturation processes and differences between generations. Now I’m beginning to think about it really as a cultural idiom of distress — it’s the way people manifest their problems through culturally relevant, culturally influenced by the culture avenues.

Two years later, in July 2012 when Zayas was interviewed by Michelle Gaitan of the San Angelo Standard-Times, he elaborated a little further in regard to his findings. This is what he said:

“It’s the cultural traditions that the immigrants bring with them from Latin America about the beliefs about what a girl should be like, things she should do, how she should behave; then her own kind of personal development — teenage years are kind of rough years in general — kids are struggling with an identity with becoming more separate from their parents; and then there is how well the family functions”

But a key question reminds in the air: what does the research and the resulting news frenzy mean by Latino culture? Does the term refer to the culture of the country of origin? To American culture? To the hybrid cultural byproduct of transnational immigration? Or something else?

The journalist from NewsTaco asked why this phenomenon is not present in the girls’ native country. Dr. Zayas responded that it may be because in their home country, they are surrounded by girls who are in “the same boat,” meaning that they share a common social system. Dr. Zayas’s answer seems rather simplistic. It implies that what Latino culture means in the US is a transplant of the culture of the countries of Latin America. Culture is conceptualized as a static, bounded, homogeneous entity, which can be carried from one place to another without changes. Dr. Zayas’s analysis also fails to include the ongoing acculturation process and resulting cultural transformation of immigrant parents, their foreign-born and US-born children, and following generations.

Cultures – Guy Catling. Posted on Tumblr.com (JAN. 5 2015) – view

Although Dr. Zayas’s answer during this interview seems to presents a fixed, essential, static understanding of Latino culture, he does point to the process of acculturation, and its impact on health. In his research, he found that suicidality rates are higher for those Latinas who were born in the US. Why do Latina girls who arrived more recently, and who therefore are presumably “less assimilated,” seem to have better outcomes when it comes to suicidality?

It is paradoxical. In his New York Times commentary, David Brooks, addressing research that points to poorer health outcomes in second and third generations of Latino immigrants, questioned whether American culture was corrupting new immigrants and not, as it is frequently argued, the other way around. A similar question underscores Cynthia Garcia Coll and Amy Kerivan Marks’s book The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents: Is Becoming American a Developmental Risk? What is in the cultural encounter between immigrants and the US host society that seems to undermine the wellbeing of those who remain in this country for generations? We may be looking for a “culture” to blame, and losing the opportunity to take a deeper look in search for more answers.

Culture and acculturation as conceptual constructs, both frequently related to mental health outcomes among Latinos, have been criticized for being very poorly defined, full of misconceptions and errors in their central assumptions, and therefore unworthy of being considered variables in health research. Other theoreticians and researchers believe that cultural explanations obscure the impact of structural factors on immigrant health disparities. However, no one denies that given the significant percentage of Latino youth who are immigrant or children of immigrants, acculturation, culture and identity are central to the understanding of the emotional and psychological well being for these youngsters.

Kirmayer says it well:

“the cultural identity of an individual must be understood in terms of ongoing interactions within multiple networks or communities; similarly, the culture of an ethnic community can only be understood in terms of its interactions with the larger society” (Kirmayer, 2012. p. 155).

Can we ask, then: Which culture is sparking and shaping the high number of Latinas contemplating suicide in the US? How would it be possible to answer this question in the context of the ongoing cultural hybridization process in which immigrants and their descendants are embedded for generations? Perhaps, a brief review of acculturation theories in relation to Latino youth mental health outcomes will help to further the discussion.

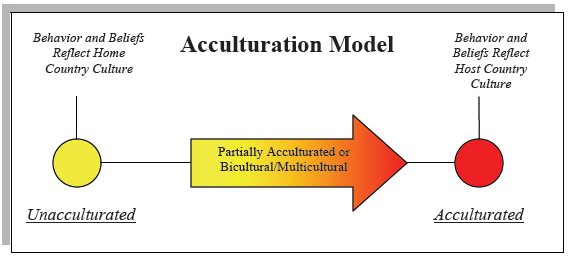

The terms acculturation and assimilation have a long history. For the purpose of this blog, the conceptualization of both terms will be borrowed from Rose M. Perez, author of the chapter “Latino Mental Health : Acculturation Challenges in Service Provision“. This is her description of the terms:

“Acculturation and Assimilation–terms used to described the complex process that immigrants go through as they incorporate into the host society’s culture– …include a range of contextual and individual -level factors that interact in ways unique to each immigrant.”

With this broad definition in mind, let’s begin our brief overview of acculturation theories utilized in the study of young Latinos and mental health outcomes.

Early research assumed that immigrants would be absorbed into the receiving society in a unilinear, unidirectional process. In this theory of assimilation, the immigrant adopts the host culture and abandones her or his cultural of origin. This was the theory that the sociologist Milton Gordon  presented in his classic 1964 book Assimilation in American Life.

presented in his classic 1964 book Assimilation in American Life.

This early account of acculturation/assimilation did not take into consideration two factors: the receiving context of the host culture and the possibility that immigrants would keep their culture of origin and at the same time would absorb the culture of the host country. This idea of biculturalism was at first seen as a liability: bicultural immigrants were described as having a “marginal” identity, in between cultures and at the margin of both.

Currently, biculturalism is seen by some authors as the wave of the future (Padilla, “Bicultural Social Development”), and these ideas seem to be represented in the media. For example, here is how the creators of the website Mitú, a digital media company for young Latinos describe their organization:

“mitú engages our audience through a Latino POV across multiple platforms. our inspiration is ‘the 200{e0067b7e5b7c4752141a12f40f20a1e8c5844cc9423417b188bf9480bfa224fe}’ – youth who are 100{e0067b7e5b7c4752141a12f40f20a1e8c5844cc9423417b188bf9480bfa224fe} American and 100{e0067b7e5b7c4752141a12f40f20a1e8c5844cc9423417b188bf9480bfa224fe} Latino. we reach a massive, cross-cultural audience who will soon be the majority of youth in the U.S.”

Despite the many critics (Padilla is one example) of the concept of marginality, some of its ideas have survived in newer models of acculturation. John Berry, a cross-cultural psychologist, created one of the most popular acculturation models, and it is used extensively in current research. According to Berry,

“the long-term consequences of the process of acculturation are highly variable, depending on social and personal variables that reside in the society of origin, the society of settlement, and phenomena that both exist prior to, and arise during, the course of acculturation. ” (p. 5)

Berry’s model is sensitive to the differences in power between the immigrant group and the host group, and in keeping with that power differential he uses the terms “dominant” and “non-dominant group.” However, in his model, it is the individual immigrants who choose one of four strategies in their acculturation process depending on whether they value maintaining their identity and characteristics and whether they value maintaining their relationship with the larger society. These “yes” and “no” orientations toward the dominant and non-dominant groups allow Berry to identify four strategies of acculturation: assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. According to Berry, immigrant youth with an integration orientation have the best psychological and sociocultural adaptation outcomes. Berry defines these four types of strategies as mutually exclusive. Since Berry is a cross-cultural psychologist, he implies that his results would apply to all immigrants, regardless of nationality, culture, or historical background.

The new wave of immigrants coming after the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965, also known as the Hart-Celler Act , which abolished an earlier quota system based on national origin and established a new immigration policy based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor to the United States, has been judged to be slow in its assimilation. This new wave of immigrants brought to the U.S. unprecedented numbers of newcomers from Latin America and Asia, changing the racial demographics of this country and triggering a backlash of nativist sentiment and anti-immigrant policies (“U.S. IMMIGRATION SINCE 1965, ” The History Channel).

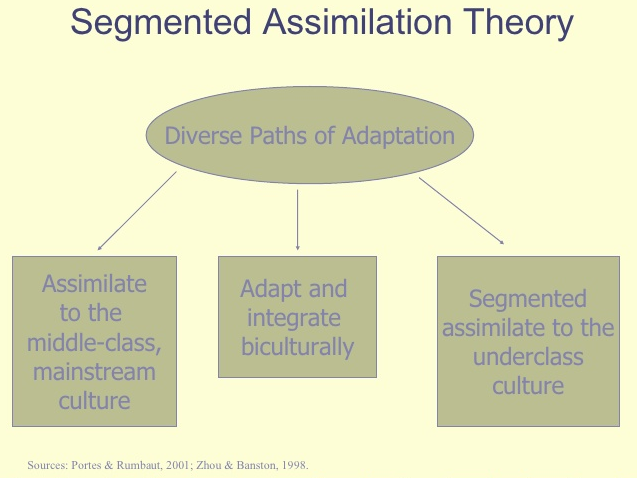

In the current racially- and sociopolitically-charged context, it is understandable that some of the new, alternative models of acculturation give greater recognition to the United States as a diverse, socially stratified society in which cultural retention and bilingualism can emerge as possible outcomes of the incorporation of immigrants (Portes Rumbaut 2001). The model of segmented assimilation is one such new effort.

Haller, Portes and Lynch, in their study “Dreams Fulfilled, Dreams Shattered: Determinants of Segmented Assimilation in the Second Generation” (2011)

“demonstrate that the assimilation of the second generation in America is neither uniform nor always benign. Distinct paths exist, some of which lead to successful integration into the mainstream, but others lead downward. These contrasting outcomes are not random, but are patterned by a set of causal forces that cumulate over time—from immigrant parents’ traits and experiences to what happens to their children in schools. Results from CILS show significant differences in education, occupation and other defining life events across major immigrant nationalities.

The analysis demonstrates that these differences are resilient and do not disappear after taking other relevant predictors, including parental human capital and family composition, into account. We believe that the most plausible explanation for these enduring national differences lies in the distinct modes of incorporation encountered by various groups in the United States. Unless one wishes to resort to theories of racial or cultural inferiority, the consistent handicaps observed among Mexican Americans and black Caribbeans—even after controlling for individual, family and school characteristics—must be linked to the unfavorable context encountered by first-generation immigrants in the United States.” (p.756)

Scholars such Portes et al. support the racial/ethnic disadvantage model, arguing that assimilation of many immigrant groups often remains blocked, leading many youngsters to follow a downward assimilation instead of assimilating to the middle class or adapting and integrating biculturally.

Perhaps acculturation is not such a universal process as Berry ( 2006) and his colleagues proposed. For instance, Bornstein’s (2017) “specificity principle” in acculturation science stands in contrast to Berry’s theory by asserting “that specific setting conditions of specific people at specific times moderate domains in acculturation by specific process” (p. 3). What he means is that the concept of acculturation has been theorized to consist of four categories: assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. In his view, the specificity principle challenges this topological construction by offering a perspective that accommodates the many variations found among contemporary migrants and their circumstances. He does not want to offer a reductionist perspective, but one that “will help to expose, explain, and appreciate the refined tapestry that acculturation is” (p. 31)

A challenge to these ideas about acculturation come from Sunil Bhatia (2002) and other postcolonial researchers who point out that because of the effects of European colonization, “Third World” immigrants construct their cultural identities as citizens of “First World” countries while simultaneously retaining strong affiliations, identification, and loyalties to the culture of their home country.The cultural hybrid self—called by others the borderland or diasporic self—performs culture by the construction of “Third World” diasporas in “First World” communities where identities are permanently contested, multiple, and constantly shifting in the ongoing negotiation and renegotiation of one’s position in relationship to others within and out of the diaspora, and in the relationship between the diaspora and the larger society.

Perhaps due to the complexity of forging one’s hybrid, borderland identity, this developmental process may become almost deadly for teenage girls with many imposed minority statuses, as is the case for young Latinas living in the US. Perhaps the tensions of living on the borderline, and of being the borderland, become even greater as your cultural loyalties become more contested when you move from first to second generation. Perhaps the right question to ask, because there is no one answer, is the question I began with: To what culture would Latina mental well-being be bound?